This page accompanies Richard Cullen Rath, “EthnoDigital Sonics and the Historical Imagination,”

in Digital Sound Studies, ed by. Mary Caton Lingold, Darren Mueller, and

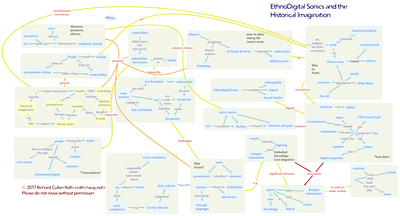

Whitney Anne Trettien (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2018), 29–46.  Here is a pretty cool VUE map that gives the architecture of the article.

The work here builds on my first article, published in 1993, Richard

Cullen Rath, “African

Music in Seventeenth-Century Jamaica: Cultural Transit and Transition,”

William and Mary Quarterly 50, no. 3 (1993): 700–726. There is more

to say on this subject in the introduction and chapter two of my book, How Early America Sounded as well.

Here is a pretty cool VUE map that gives the architecture of the article.

The work here builds on my first article, published in 1993, Richard

Cullen Rath, “African

Music in Seventeenth-Century Jamaica: Cultural Transit and Transition,”

William and Mary Quarterly 50, no. 3 (1993): 700–726. There is more

to say on this subject in the introduction and chapter two of my book, How Early America Sounded as well.

I have been working on three pieces of African music from seventeenth-century Jamaica that are notated in Hans Sloane’s Voyage to the Islands, a rare book published in 1704 about his trip to Jamaica and other parts of the Caribbean in 1688. The transcriptions are interesting because they contain features that were not present in Western music of the time, including particular forms of syncopation and polymeter, microtonal blues scales (which can be heard in the third section of “Koromanti), and more. Here is a quick sonic tutorial on polyrhythm and polymeter

The Angola piece is made of two interlocking parts played in quite different scales. It was most likely played on the banjo-like instrument (bass) and the harp-like instrument on the left. Part of it resembles the music of the Angola region, but the other part does not. Probably this piece was played by two musicians who were from different places. Perhaps neither was entirely pleased with the way things turned out, although to our ears, which have grown used to this particular combination (It sounds quite good cranked up on an electric guitar and bass actually!), it sounds fine. The musicians in this piece had not internalized the mixing of West African styles as in Koromanti, so my guess is that this piece was played by more recent arrivals. This piece is not in its final form yet…I just sketched it by playing two guitars.

The instrumentation in the “Koromanti” piece is more accurate. I made a wooden keyed thumb piano from an old dresser drawer with nice tone and a bunch of the little sticks that used to go in new women’s shoes to hold the paper in the toe and keep the shape (I worked in a shoe store a long time ago). I then tuned it and sampled it, three different velocities for each note, and played the samples in a sequencer, which allowed me to get the music down exactly as transcribed (seeing as I am not much of a mbirist). The microtones are particularly interesting, because they turn up in the third part of “Koromanti” as sometimes one note and sometimes another that make a totally messed up eight note scale. If the notes are instead read as a microtone that the transcriber did not know what to do with, you are left with a seven-note bluesy scale with a slightly flatted major third and a dominant seventh. Koromanti was most likely not an “authentic” (whatever that means) West Ghanaian song as the title would indicate. Rather it was creolized, showing evidence of traits from other parts of west Africa, perhaps indicating that the musician had been in the Americas for some time and heard and absorbed music from other parts of West Africa too. I am pretty sure the instrument was a thumb piano.

Below is a model of the neglected process of pidfinization that I work through in the 1993 article. Enslaved people underwent the process of pidginization in their first generation (this first generation could last a long time as new people were brought into the plantations over time). The Middle passsage and slavery severely disrupted natal cultures but obviously they would not be erased. Pidgin identities took shape in this crucible largely through improvisation, negotiation, and making do. Pidginization existed as much in the relations as in the people and was generally volatile, although some conventions could take hold that varied by place and time.

When children were born into this situation, they turned these volatile cultures into a new natal culture, stabilizing it in the process. This second (abstract) generation created new languages and cultures from the pidginized environment through the process of creolization, which generally had a stabilizing influence that could in turn shape the pidginization process that it grew out of. This was the process of creolization and resulted in the creole cultures we know of today in the Caribbean and North America.